In an age when few dared to travel beyond known boundaries, Ibn Battuta’s journey started as a pilgrimage to Mecca. It became an astonishing three decade quest to the depths of the unknown and ended with a monumental travelogue.

Dubbed by many as the world’s greatest traveller, the travels of Ibn Battutah surpassed those of his near-contemporary Marco Polo in both distance and duration. While Polo’s travels were primarily through Asia and the court of Kublai Khan, Ibn Battuta encompassed not only Asia but also North and West Africa, Southern and Eastern Europe, the Arabian Peninsula, Central and Southeast Asia, India and China.

This distinction often draws comparisons and links between Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo, highlighting their unique contributions to the understanding of the mediaeval world. Battuta’s travels were driven by both religious devotion and an insatiable curiosity about the cultures, peoples, and governance systems he encountered.

However, Ibn Battuta’s accounts have not been without their critics. Some modern historians have raised doubts about the authenticity and accuracy of his descriptions, questioning whether he could have possibly visited all the places he claimed.

Let’s step back in time to the fourteenth century in an attempt to shed light on the remarkable footsteps of Ibn Battuta.

The Early Life of Ibn e Batuta

Portrait of Ibn Battuta (Credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Very little is known about the early life of Ibn Battuta, sometimes known as Ibn e Batuta or Ibn Battutah.

It’s believed he was born in Tangier – modern-day Morocco – in February 1304 into a Muslim Berber family of legal scholars known as qadis. It’s likely he studied at a school of Islamic jurisprudence, but in 1325 at the age of twenty-one he set out on a pilgrimage – hajj – to Mecca. It seems his original intention was to fulfil his religious duty, study under a number of eminent scholars and then return home, but it didn’t quite work out like that.

A passion for travel overtook him and he started to wander the Earth. Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo – albeit Marco Polo travelled thirty or so years before – were similar but different. Both extraordinary explorers, but the Venetian travelled for trade and education. Ibn Battuta travelled not to fulfil an obligation or mission, nor to reach a specific destination. He arguably travelled for the pure joy it gave him.

The Travels of Ibn Battutah - The First Itinerary

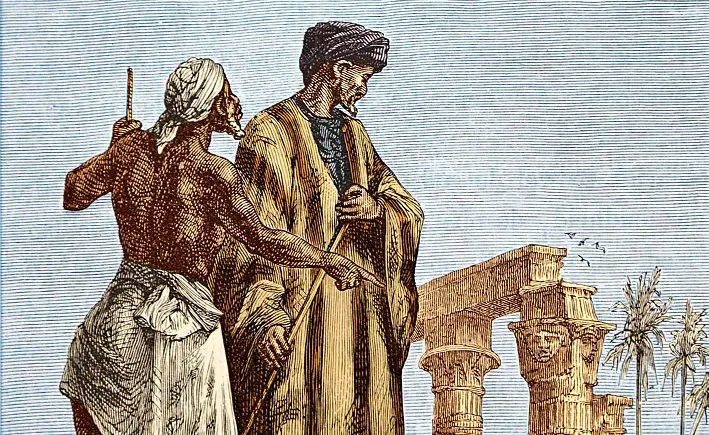

Ibn Battuta in Egypt. (Credit: Heritage Images / Contributor via Getty Images)

Ibn Battuta’s journey is generally broken up into three itineraries. The first, from 1325 until 1332 took him through North Africa, Iraq, Iran and elsewhere in the Arabian Peninsula, and down Africa’s east coast.

His first journey to Mecca, of which there were many, took him to Algeria and onto Tunisia. Here he got married, but soon left his new wife due to a dispute with her father. He then went to Alexandria in Egypt and then, on arriving in Cairo, he called it ‘peerless in beauty and splendour’.

Ibn Battuta then joined a caravan which took him as far as Medina. From there he completed his pilgrimage to Mecca. He was supposed to go home at this point, but decided instead to continue on. He travelled to Iraq and Iran in the summer of 1327 and sometime around September or October of that year, he went back to Mecca performing his second hajj.

It’s not clear in his chronicle but he either left Mecca in 1328, or stayed three years and left in 1330, but his next stops took him to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. From there he took a series of boats south to Yemen and then down the eastern coast of Africa to Mogadishu in Somalia, a place he described as ‘an exceedingly large city’ known as Balad al-Barbar, or the ‘Land of the Berbers’.

From there, he went back to Mecca to perform a third hajj, either in 1330, or as the timeline suggests, most likely in 1332.

Ibn Battuta’s Journey - The Second Itinerary

The second itinerary, from 1332 until 1347 saw him travel across the Black Sea area, through Central Asia, India, Southeast Asia and China.

This period of Ibn Battuta’s journey is particularly challenging to detail accurately due to the mix of eyewitness accounts and second-hand information in his book. Some scholars suggest the confusion in the timeline could be due to the way Ibn Battuta recounted his stories to his scribe, Ibn Juzayy, years after the actual events. Despite these uncertainties, his account provides a rich and vivid picture of the mediaeval world.

After his third pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibn e Batuta travelled north to the Black Sea region, visiting Anatolia (present-day Turkey). He may have also journeyed to Crimea and the Golden Horde region along the Volga River. He returned to Mecca briefly and then set off for a long journey towards India. This journey led him across Persia (Iran) and Afghanistan. He likely travelled through cities like Shiraz, Herat, and Kabul.

Ibn Battuta arrived in India and spent an extended period in the Delhi Sultanate, under the patronage of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq. He travelled extensively across the Indian subcontinent, visiting places like Bengal and the Malabar Coast.

It’s believed he spent as many as six years in India and, in around 1341, he was sent as an ambassador to China by the Sultan of Delhi. However, his journey was interrupted by pirates where he was almost killed. He went back to India and from there to the Maldives, where he stayed for about a year working as a judge and marrying into the royal family.

From the Maldives to Sri Lanka and from there the travels of Ibn Battutah took him to Bengal and Sumatra, eventually reaching the Chinese port of Quanzhou in the Fujian province around 1345. His descriptions of China include visits to Guangzhou, Hangzhou – which he described as one of the biggest cities he’d ever seen- and possibly even Beijing, although the exact details and sequence of these visits are uncertain.

The Return to Morocco

A tiled fountain on Mosque Hassan in Rabat, Morocco. (Credit: Richard Sharrocks via Getty Images)

Ibn Battuta’s return journey from China to Morocco, marking the final leg of his extensive travels, is a fascinating segment of his adventures, however it’s the aspect of his journey that is the most debated by academics and historians. Although the exact route and timeline are somewhat unclear due to inconsistencies in his accounts, the general outline of his journey effectively retraced his steps through Southeast Asia, back through Persia and the Middle East.

He then travelled across the North African coast and back to Morocco. At some point after his return it’s said he was sent by the Sultan of Morocco to Granada, the heartland of Muslim Spain.

The Rihla

Close-up of an old opened book in a historic library. (Credit: Westend61 via Getty Images)

There is one single account for the travels of Ibn Battutah, the book called A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling, otherwise known as Rihla, or The Travels.

It was said he made no notes in the thirty years he was on the road and the book was dictated to a scholar he met in Granada named Ibn Juzayy. He relied on memory as well as manuscripts written by travellers who went before him. This has led scholars to have raised several specific issues regarding the authenticity of all the places Ibn Battuta claims to have visited.

Chronological and Geographical Inconsistencies

Some parts of the narrative contain chronological and geographical inconsistencies. For instance, the timeline of his travels in certain regions appears compressed or extended in a way that seems unrealistic. Additionally, the sequence of visits to some places does not align logically with the travel times and routes known from that period.

Second-Hand Information & Hearsay

There are suspicions that Ibn Battuta included accounts of places and events that he heard about from others but did not experience firsthand. This is particularly suspected in the sections about China and parts of Central Asia, where his descriptions sometimes seem more like compilations of other travellers’ tales rather than his own observations. For example, the descriptions of a number of locations in the Middle East are remarkably similar versions of accounts by Ibn Jubayr and Muhammad al-Abdari who travelled in the late thirteenth century.

Lack of Detailed Descriptions

In some instances, Ibn Battuta provides only vague or generic descriptions of certain places, lacking specific details that would indicate a personal visit. This has led some scholars to question whether he actually visited these locations. In addition, some descriptions of customs, cultures, and societal structures in various regions occasionally contain inaccuracies or exaggerations. These anomalies raise doubts about whether Ibn e Batuta fully understood or directly experienced these aspects.

Despite these issues, it’s important to note that many historians and scholars still regard Ibn Battuta’s Rihla as a valuable and accurate historical document. While there may be embellishments or occasional inaccuracies, the work provides an important perspective on the fourteenth century world, especially in relation to the Islamic societies and cultures he encountered. The Rihla remains a vitally important source for understanding the history, geography, and cultural and religious landscape of the mediaeval period.

Like his early years, very little is known of his life after the Rihla was finished around 1355. It’s believed he was made a judge in his home country of Morocco and died around 1369, aged 64 or 65.

The 75,000 Mile Man: The Travels of Ibn Battuta

Illustration of Ibn Battuta (Credit: Dorling Kindersley via Getty Images)

Ibn Battuta’s extraordinary journey encompassing vast swathes of the mediaeval world, stands as a remarkable testament to human curiosity and resilience. Despite the debates surrounding the veracity of his accounts, his narrative in the Rihla offers an invaluable window into the diverse cultures, societies, and landscapes of the fourteenth century.

His travels surpass mere physical exploration, delving into the realms of cultural exchange, religious devotion, and intellectual curiosity. The legacy of men like Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo endure through centuries and continue to inspire and educate, embodying the spirit of exploration and the timeless quest for knowledge and understanding of the world beyond one’s own horizons.